A group of companies that includes Mozilla (Firefox) and DuckDuckGo launched a privacy initiative called Global Privacy Control (GPC). A new browser specification, it’s intended to simplify and expedite consumer privacy requests under the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). Publishers that have signed on include the New York Times, Washington Post and the Financial times.

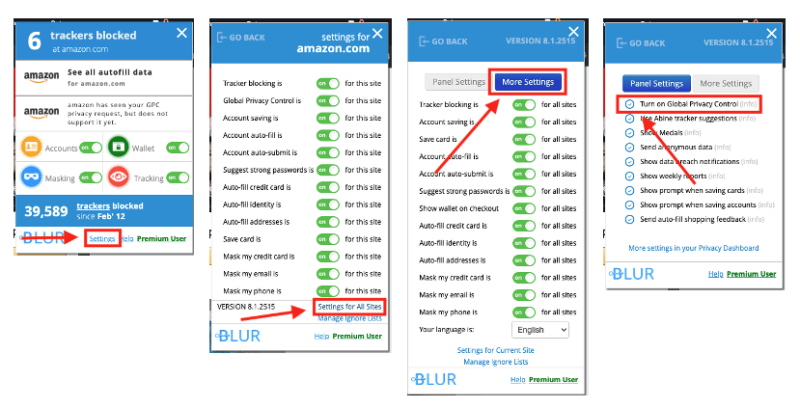

GPC is integrated into Brave and the DuckDuckGo mobile browser. There are also browser extensions from DuckDuckGo, Abine, EFF and Disconnect. Abine works with Chrome.

Based on user settings, the browser or extension will send a signal to publisher sites. According to GPC, “This signal communicates a Do Not Sell request as outlined in CCPA regulations and conveys a general request that data controllers limit the sale or sharing of the user’s personal data, as outlined in the GDPR.”

Not unlike ‘do not track.’ If it reminds you of the ill-fated “do not track” (DNT) initiative that’s because it’s quite similar in many respects. DNT was a browser-based attempt to communicate privacy preferences to publishers. It was largely ignored by big publishers and ad-tech companies, including Google, Facebook, Yahoo and Microsoft.

GPC is totally voluntary. And just like DNT publishers can choose to disregard it.

I asked Rob Shavell, Abine CEO, why publishers would want to be a part of the GPC initiative. He said, “By complying with this standard, they can avoid some compliance costs and burdens [of CCPA and GDPR].” While not compliance in itself, he added that participation would potentially be helpful in making the case they’re compliant with CCPA. Shavell also said that being a part of GPC would help create “goodwill and trust” among consumers and could lead to greater loyalty for publishers.

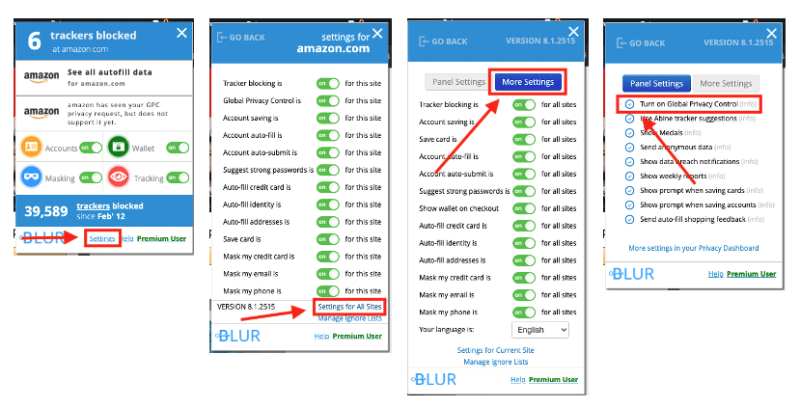

Abine’s Blur browser extension with GPC

Although not intended to, CCPA and Europe’s GDPR rules as implemented place a significant burden on consumers to navigate confusing cookie choices (GDPR) or to walk through a cumbersome process for each site visited (CCPA). Consumers often wind up “accepting all” cookies or not pursuing “do not sell,” if they can find the link in the first place.

This is by design. Many publishers are complying with the letter but not the spirit of these laws. They recognize that by making it more challenging for consumers, they will likely be passive and accept cookies or not prevent their data from being sold.

Getting publishers on board will be challenging. GPC seeks to simplify and remove friction from the process of exercising privacy rights. Unlike ad blocking, GPC is an entirely “pro bono” effort. It doesn’t have a revenue mode, although the individual involved companies clearly do. For example, Abine makes money by selling consumer subscriptions to its premium privacy products.

GPC faces the challenge of building a two-sided marketplace; it needs both publishers and consumers to embrace it. Consumer adoption will be challenging, but publishers will be tougher to win over because they have no clear commercial incentive to adopt GPC.

Shavell, like many others, argues it’s in the industry’s best interest to embrace privacy and not resist it. He says that the current zero-sum conversation between privacy advocates and marketers is limited and limiting. “You’d find a lot of willingness of consumers to engage with marketers and brands but there’s this binary, uncreative conversation happening. It needs to change and it will over time.”

Why we care. Shavell says that consumers have more nuanced and sophisticated privacy views than martech companies fear. As evidence, he says that in the week since launch, only 32% of consumers using Abine’s browser extension have activated “do not sell.” Admittedly, this data is very preliminary. However, a survey we conducted on IDFA deprecation supports Abine’s early data. Nearly 60% of consumers in that survey said they were open to allowing tracking.

Publishers may be able to negotiate with consumers and offer incentives in exchange for their data. Many past surveys, including ours, show this could be effective.

GPC may or may not succeed but the problems it seeks to solve won’t go away. As Shavell suggests, the industry should have a direct and respectful conversation with consumers about privacy. If they don’t they’ll probably continue to face “hostile” legislation such as California’s forthcoming California Privacy Rights Act.

This story first appeared on MarTech Today.

The post Global Privacy Control group aims to succeed where ‘do not track’ failed appeared first on Search Engine Land.

Source: IAB