January 2020 felt like a turning point. CCPA went into effect, Google Chrome became the latest browser to commit to a cookie-less future and, after months of analytics folks sounding the alarm, digital marketers sobered to a vision of the future that looks quite different than today.

This article is not a complete history of consumer privacy nor a technical thesis on web tracking, although I link to a few good ones in the following paragraphs.

Instead, this is the state of affairs in our industry, an assessment of where search marketers find themselves in the current entanglement of data and privacy and where we can expect it to go from here.

This is also a call to action. It’s far from hyperbole to suggest that the future of digital and search marketing will be greatly defined by the actions and inactions of this current calendar year.

Why is 2020 so important? Let’s assume with some confidence that your company or clients find the following elements valuable, and review how they could be affected as the associated trends unfold this year.

- Channel attribution will stumble as tracking limitations break measurability and show artificial performance fluctuations.

- Campaign efficiency will lose clarity as retargeting efficacy diminishes and audience alignment blurs.

- Customer experience will falter as marketers lose control of frequency capping and creative sequencing.

Despite the setbacks, it is not my intention to imply that improved regulation is a misstep for the consumers or companies we serve. Marketing is at its best when all of its stakeholders benefit and at its worst when an imbalance erodes mutual value and trust. But the inevitable path ahead, regardless of the destination, promises to be long and uncomfortable unless marketers are educated and contribute to the conversation.

That means the first step is understanding the basics.

A brief technical history of web tracking (for the generalist)

Search marketers know more than most about web tracking. We know enough to set people straight at dinner parties — “No, your Wear OS watch is not spying on you” — and follow along at conferences like SMX when a speaker references the potentially morbid future of data management platforms. Yet most of us would not feel confident in front of a whiteboard explaining how cookies store data or advising our board of directors on CCPA compliance.

That’s okay. We’ve got other superpowers, nice shiny ones that have their own merit. Yet the events unfolding in 2020 will define our role as marketers and our value to consumers. We find ourselves in the middle of a privacy debate, and we should feel equipped to participate in it with a grasp of the key concepts.

What is the cookie?

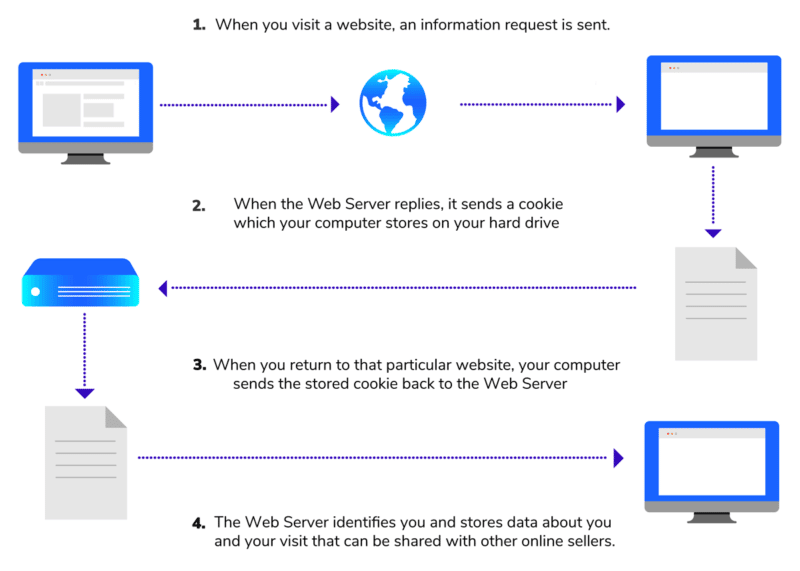

A cookie stores information that is passed between browser and server to provide consistency as users navigate pages and sites. Consistency is an operative word. For example, that consistency can benefit consumers, like the common shopping cart example.

Online shoppers add a product to the cart and, as they navigate the site, the product stays in the shopping cart. They can even jump to a competitor site to price compare and, when they return, the product is still in the shopping cart. That consistency makes it easier for them to shop, navigate an authenticated portion of a site, and exist a modern multi-browser, multi-device digital world.

Consistency can also benefit marketers. Can you imagine what would happen to conversion rates if users had to authenticate several times per visit? The pace of online shopping would grind to a crawl, Amazon would self combust, and Blockbuster video would rise like a phoenix.

But that consistency can violate trust.

Some cookies are removed when you close your browser. Others can accrue data over months or years, aggregating information across many sites, sessions, purchases and content consumption. The differences between cookie types can be subtle while the implications are substantial.

Comparing first- and third-party cookies

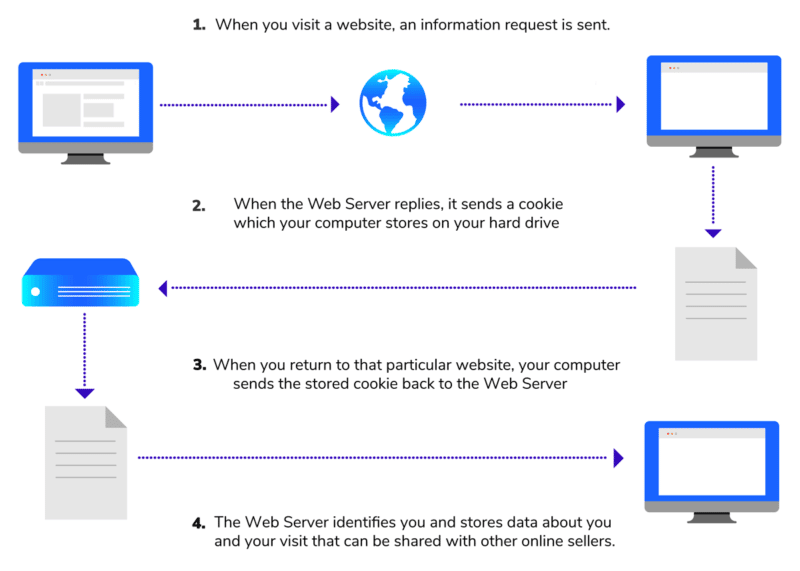

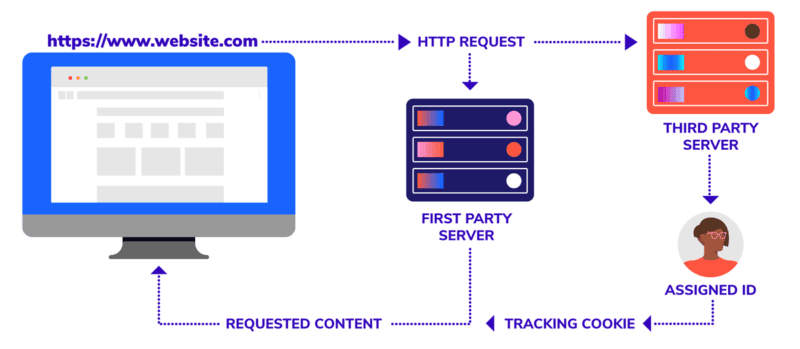

It is important for marketers to understand that first- and third-party cookies are written, read and stored in the same way. Simo Ahava does a superb job expanding on this concept in his open-source project that is absolutely recommended reading. Here’s a snippet.

It’s common in the parlance of the web to talk about first-party cookies and third-party cookies. This is a bit of a misnomer. Cookies are pieces of information that are stored on the user’s computer. There is no distinction between first-party and third-party in how these cookies are classified and stored on the computer. What matters is the context of the access.

The difference is the top-level domain that the cookie references. A first-party cookie references and interacts with the one domain and its subdomains.

- searchengineland.com

- searchengineland.com/staff

- events.searchengineland.com

A third-party cookie references and interacts with multiple domains.

- searchengineland.com

- events.marketingland.com

- garberson.org/images

Marketing Land has a helpful explainer, aptly called WTF is a cookie, anyway? If you’re more of a visual learner, here is a super simplistic explanation of cookies from The Guardian. Both are from 2014 so not current but the basics are still the basics.

Other important web tracking concepts

Persistent cookies and session cookies refer to duration. Session cookies expire at the end of the session when the browser closes. Persistent cookies do not. Data duration will prove to be an important concept in the regulation sections.

Cookies are not the only way to track consumers online. Fingerprinting, which uses the dozens of browser and device settings as unique identifiers, has gotten a lot of attention from platform providers, including a foreshadowed assault in Google’s Privacy Sandbox announcement.

Privacy Sandbox is Google’s attempt at setting a new standard for targeted advertising with an emphasis on user privacy. In other words, Google’s ad products and Chrome browser hope to maintain agreeable levels of privacy without the aggressive first-party cookie limitations displayed by other leading browsers like Safari and Firefox.

Storage is a broad concept. Often it applies to cookie storage, and how browsers can restrict the storage of cookies, but there are other ways to store information. LocalStorage uses Javascript to store information in browsers. It appeared that alternate storage approaches offered hope for web analysts and marketers affected by cookie loss until recent browser updates made those tactics instantly antiquated.

Drivers: How we got here

It would be convenient if we could start this story with one event, like a first domino to fall, that changed the course of modern data privacy and contributed to the world we see in 2020. For example, if you ask a historian about WWI, many would point to a day in Sarajevo. One minute Ol’ Archduke Ferdinand was enjoying some sun in his convertible, the next minute his day took a turn for the worse. It is hard to find that with tracking and data privacy.

Facebook’s path to monetization certainly played a part. In the face of market skepticism about the social media business model, Facebook found a path to payday by opening the data floodgates.

While unfair to give Facebook all the credit or blame, the company certainly supported the narrative that data became the new oil. An iconic Economist article drew several parallels to oil, including the consolidated, oligopolistic tendencies of former oil giants.

“The giants’ surveillance systems span the entire economy: Google can see what people search for, Facebook what they share, Amazon what they buy,” the Economist wrote. “They own app stores and operating systems, and rent out computing power…”

That consolidation of data contributed to an increase in the frequency and impact of data leaks and breaches. Like fish in a bucket, nefarious actors knew where to look to reap the biggest rewards on their hacking efforts.

It was a matter of time until corporate entities attempted to walk the blurring line of legality, introducing a new weaponization of data that occurred outside of the deepest, darkest bowels of the internet.

Enter Cambridge Analytica. Two words that changed the way every web analyst introduced themselves to strangers. “I do analytics but, you know, not in, like, a creepy way.”

Cambridge Analytica, the defunct data-mining firm entwined in political scandal, shed a frightening light on the granularity and unchecked accessibility of platform data. Investigative reporting revealed to citizens around the world that their information could not only be used by advertising campaigns to sell widgets, but also by political campaigns to sell elections. For the first time in many homes, the effects of modern data privacy became tangible and personal.

Outcomes: Where we are today

The state of data privacy in 2020 can perhaps best be understood by framing it in terms of drivers and destinations. Consumer drivers, like those mentioned in the previous section, created reactions from stakeholders. Some micro-level outcomes, like actions taken by individual consumers, were predictable.

For example, the #deletefacebook hashtag first trended after the Cambridge Analytica story broke and surveys found that three-quarters of Americans tightened their Facebook privacy settings or deleted the app on their phone.

The largest outcomes are arguably happening at macro levels, where one (re-)action affects millions or hundreds of millions of people. We have seen some of that from consumers with the adoption of ad blockers. For publishers and companies that live and die with the ad impression, losing a quarter of your ad inventory due to ad blockers was, and still is, devastating.

Political Outcomes

Only weeks after Cambridge Analytica found its infamy in the headlines, the European Union adopted GDPR to enhance and defend privacy standards for its citizens, forcing digital privacy discussions into both living rooms and board rooms around the world.

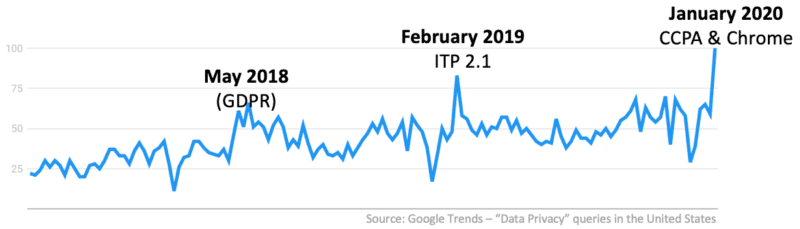

Let’s use the following Google Trends chart for “data privacy” in the United States to dive deeper into five key outcomes.

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has handed out more than €114 million in fines to companies doing business in the EU since becoming enforceable in May 2018. It’s been called “Protection + Teeth” in that the law provides a variety of data protection and privacy rights to EU citizens while allowing fine enforcement of up to €20 million or 4 percent of revenue, whichever hurts violators the most.

Months later, the United States welcomed the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which went into effect in January 2020 — becoming enforceable in July. Similar to GDPR, a central theme is transparency, in that Californians have the right to understand which data is collected and how that data is shared or sold to third parties.

CCPA is interesting for a few reasons. California is material. The state represents a double-digit share of both the US population and gross domestic product. It is also not the first time that California’s novel digital privacy legislation influenced a nation-wide model. The state introduced the first data breach notification laws in 2003, and other states quickly followed.

California is not alone with CCPA, either. Two dozen US state governments have introduced bills around digital tracking and data privacy, with at least a dozen pending legislation. That includes Nevada’s SB220 which became enacted and enforceable within a matter of months in 2019.

Corporate Outcomes

Corporate responses have come in many forms, from ad blockers I mentioned to platform privacy updates to the dissolution of ad-tech providers. I will address some of these stories and trends in the following section, but, for now, let’s focus on the actions of one technology that promises to trigger exponential effects on search marketing: web browsers.

The Safari browser introduced Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP) in 2017 to algorithmically limit cross-site tracking. Let’s pause to dissect the last few words in that sentence.

- Algorithmically = automated decisions that prioritize scale over discernment

- Limit = block immediately or after a short duration

- Cross-site tracking = first- and third-party cookies

ITP 1.0 was only the beginning. From there, the following iterations tightened cookie duration, storage, and the role of first-party cookies for web analytics. Abigail Matchett explains the implications for users of Google Analytics.

“All client-side cookies (including first-party trusted cookies such as Google Analytics) were capped to seven days of storage. This may seem like a brief window as many users do not visit a website each week. However, with ITP 2.2 and ITP 2.3… all client-side cookies are now capped to 24-hours of storage for Safari users… This means that if a user visits your site on Monday, and returns on Wednesday, they will be granted a new _ga cookie by default.”

You are beginning to see why this is a big deal. Whether intended or not, these actions reinforce the use of quantitative metrics rather than quality measures by obstructing attribution. There is far more than can be said on ITP so if you are ready for a weekend read, I recommend this thorough technical assessment of the ITP 2.1 effects on analytics.

If ITP got marketer’s attention, Google reinforced it by announcing that Chrome would stop supporting third-party cookies in two years, codifying for marketers that cookie loss was not a can to be kicked down the road.

“Cookies have always been unreliable,” Simo Ahava told me. “To be blind-sided by the recent changes in web browsers means you haven’t been looking at data critically before. We are entering a post-cookie world of web analytics.”

Where it goes from here

The state of tracking and data privacy can take several paths from here. I outline a few of the most plausible then ask others in the analytics and digital space to offer their insights and recommendations.

2020 Path A: Lack of clarity leads to little change from search marketers

This outcome seemed like a real possibility in the first week of January as California enacted CCPA while enforcement deadlines got delayed. It was not yet clear what enforcement would look like later in the year and it appeared, despite big promises, that tomorrow would look a lot like today.

This path looked less likely after the second week of January. That leads us to the next section.

2020 Path B: Compounding tracking limitations keep marketers on their heels

Already in 2020 we have seen CCPA take effect, Chrome put cookies on notice, stocks for companies that rely on third-party cookies tumble, and the sacrifice of data providers that threatened consumer trust.

And that’s just January.

2020 Path C: Correction as consumer fear eases in response to industry action

The backlash to tracking and privacy is a reaction to imbalance. Consumers are protecting their data, politicians are protecting their constituents, and platforms are protecting their profits. As difficult as it is to see from our vantage point today, it’s most likely that these imbalances will normalize as stakeholders feel safe. The question is how long it will take and how many counter adjustments are required in the wake of over or under correcting.

As digital marketers, who in some ways represent both the consumers with whom we identify and the platforms with whom we depend, are in a unique position to expedite the correction and return to balance.

Finally, I would like to congratulate Simon Poulton on the birth of his first child, Matthew. We started writing this article together then someone wonderful decided to show up early. We all look forward to seeing you again at SMX someday soon. Congrats, Simon.

The post The state of tracking and data privacy in 2020 appeared first on Search Engine Land.

Source: IAB